This piece is part 2 of a 4 part series on behaviour change that was researched, written and designed as part of the Fuller Fellowship program. The series looks at behaviour change through the lens of human-centred design, and provides insights and guidance for communicators, designers, or anyone hoping to impact real, long-term behaviour outcomes for humans.

In the 1970s, a group of researchers set out to understand the effects of rewards on the behaviour of children. They picked a group of young kids observed to enjoy drawing in their spare time, and assigned them to one of three conditions.

In the ‘expected’ condition, children were told that they would be rewarded for drawing with a certificate, and were then rewarded as promised. In the ‘unexpected’ condition, children were not told they’d receive a certificate, but received one anyway. In the control group, children were asked if they wanted to draw, but not promised or given any reward.

Two weeks later, to the surprise of the researchers, not only did the kids who received no incentive display the same enthusiasm and time engaged in drawing, those children in the ‘expected’ reward condition became the most disengaged with the task.

Similar experiments have been repeated with adults and children for a range of self-motivated tasks, such as problem solving, reading, and playing musical instruments, showing the same results. That extrinsic rewards were met with diminished intrinsic motivation.

When we want to change behaviour, our first instinct might be to punish wrongdoers, and reward do-gooders. But research shows us that motivation is multifaceted, and the wrong approach to behaviour change interventions can not only render carrots and sticks ineffective, but actually make matters worse.

In this article, we’ll be diving into the science behind motivation, and how to foster self-driven, long lasting motivation via a human-centred design approach.

Extrinsic vs Intrinsic Motivation

Extrinsic motivation to do a particular behaviour is triggered by the promise of a reward (carrots), and diminished by the threat of a punishment (sticks). This process of reinforcing behaviour, or deterring it, is known as operant conditioning.

Cassinos and social media platforms take this one step further and reinforce behaviour via a variable ratio schedule. This means behaviours are rewarded unpredictably. Sometimes you push a button and get a reward, sometimes you get nothing. That prospect of knowing that you might get something is what keeps us hooked.

Check phone -> No alerts -> Notification from friend = social validation -> Check phone

Carrots and sticks work. Consider how many people would quit their jobs tomorrow if they won the lottery. However, they’re not always the best method for achieving results.

Why? Because the prospect of a reward changes the story from one of ‘I’m doing this because I want to’, to ‘I’m doing this for the reward’. It turns a once potentially desirable or purposeful task into one motivated by money, free beer, bonus screen time, or whatever incentive was promised.

Extrinsic rewards have also been shown to narrow our focus and reduce capacity for out-of-the-box thinking and long-term planning and decision making. It prompts fast, intuitive, thinking over slow, deliberate thinking.

When we want to reinforce unconscious habits, can continually provide rewards long-term, or incentives are expected or ethically necessary (eg. labour for profit), extrinsic rewards may be the answer.

When we want people to make better decisions, consider the broader implications of actions beyond themselves in the current moment, and willingly engage in behaviours without constant reward, leveraging intrinsic motivation may have the best outcome. That is, working with personal values and drivers that make people actually want to do the behaviour.

Self Determination Theory

The term self-determination theory was coined by behavioural scientists Richard M. Ryan and Edward L. Deci. It proposes that for intrinsic motivation to be incited, three core needs must be satisfied..

Autonomy

Having choice and control over how, when, and with who we work towards our goals – ‘I am in control of my journey to success’.

Competence

Our literal ability as well as our perceived capability to perform a behaviour – ‘I can feel gratified by the progress I’m making and confident in my ability to do this’.

Relatedness

A sense of connection and belonging within society, and a sense of purpose beyond personal gains – ‘I feel that what I am doing is of benefit to others, and is important for my sense of identity’.

By meeting these needs, we can change someone’s motivational story from ‘I don’t want to do this’, or ‘I should do this…’ to ‘I want to do this’.

Empowering Behaviour Change

How many times have you taken up a new hobby and realised, you suck. Immediately, you are the worst violinist / bread maker / taxidermist you ever will be. But then.. You get better. You observe growth, and feel a great sense of joy and empowerment.

What about a time where you tried something new, you sucked, you never did it again. Your likelihood of overcoming this first hurdle is largely dependent on whether you have a growth mindset, or a fixed mindset.

A growth mindset sees skills and strengths as something you can grow if you work at them. A fixed mindset is rooted in having set strengths and weaknesses that you cannot change.

In order to induce a growth mindset from our audience, we need to give them evidence that applied effort will lead to progress. Provide opportunities to succeed early and often. Consider a simple challenge that is just difficult enough for a beginner, then, keep raising the bar. Provide ways for your audience to observe the progress they have made and how they’re tracking towards a goal. Give regular praise and feedback along the way. This sense of progress taps into our desire for competence.

Giving people agency over their own behaviour change journey is also conducive to growth. Studies show autonomous motivation can lead to better conceptual understanding, academic performance, persistence, productivity, and psychological well-being, as well as reducing burnout. Having choice over what we do when and how we do it taps into our desire for autonomy.

Even communications and storytelling can tap into the satisfaction that comes from ‘working for one’s meal’. Rather than nagging our audience to do what we want, we can tell compelling stories that help to edit existing views and prompt people to make behaviour changes of their own volition.

Combined, meeting autonomy and competence needs leads to increased sense of self-efficacy, which is linked with better long-term behaviour outcomes, and ability to recover from slip ups.

Social Norms

Humans need to belong. The bonds we share, how we are viewed and valued by others, and our sense of identity are important for finding our place and purpose within our tribe.

One way we pursue the acceptance of others is by prescribing to social norms. Social norms are the behaviours and customs we collectively believe to be appropriate in a specific context. They can vary greatly across cultures and generations, and are developed as part of our social schemas.

Social norming also impacts the way we interpret messages about what we shouldn’t be doing in a very interesting way. Research shows us that the more widespread we perceive a behaviour to be (whether accurate or not), the more likely we are to join in. When we are told not to do something, we believe that lots of other people must be doing it, and therefore we should/can too. This bandwagon effect can see behaviour change messaging cause a rise in the undesired behaviour.

Whilst our desire to fit in can lead us astray, it can also be leveraged. For example, we can raise awareness of how other people are doing the right thing.

Behaviour Change Success Stories

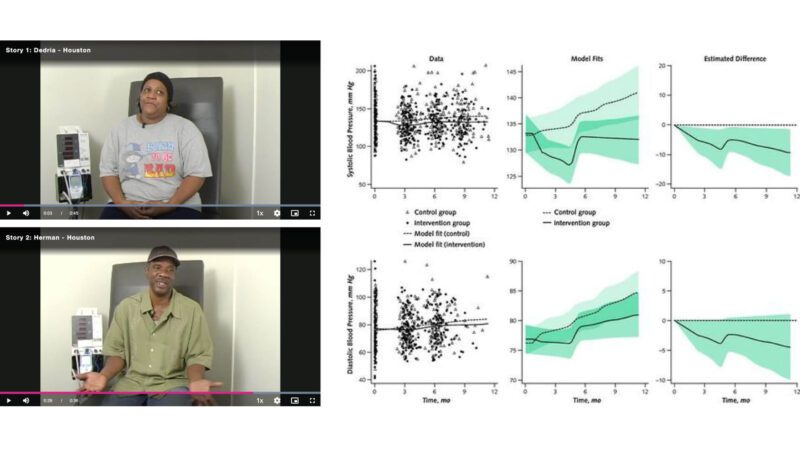

In 2011, researchers in the US wanted to test the idea that culturally appropriate storytelling could have real impacts on health behaviours. The study compiled videos of African Americans, a demographic disproportionately affected by high blood pressure, talking about their experience battling hypertension. Participants, also African Americans with high blood pressure, watched the videos along with follow up information on what they could do to see health improvements. The storytelling intervention saw a significant reduction in blood pressure for participants in the 12 months following, greater than that of some pharmaceutical interventions. These results speak to the power success stories from people we relate to have on our relatedness and competence driven motivation.

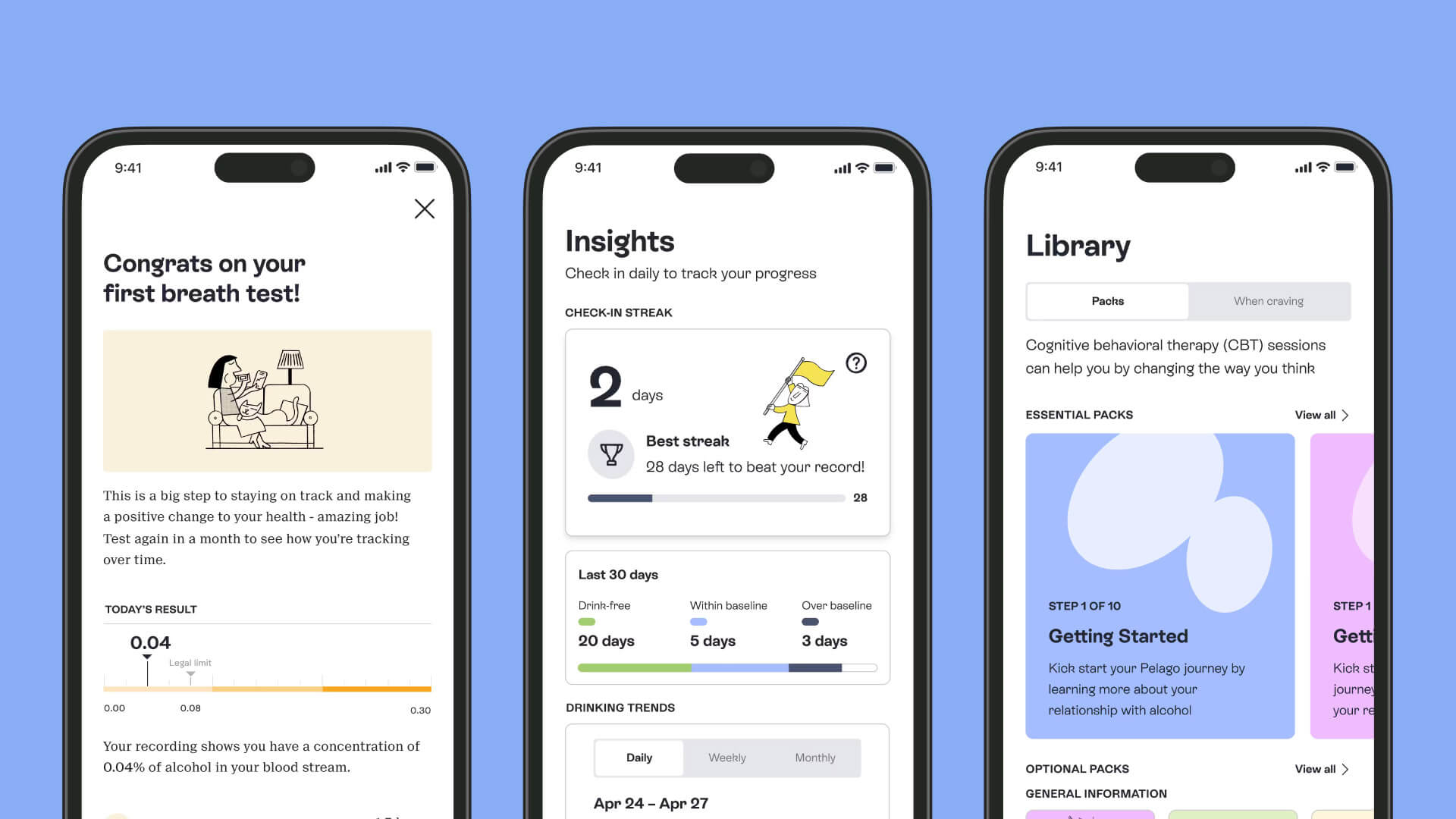

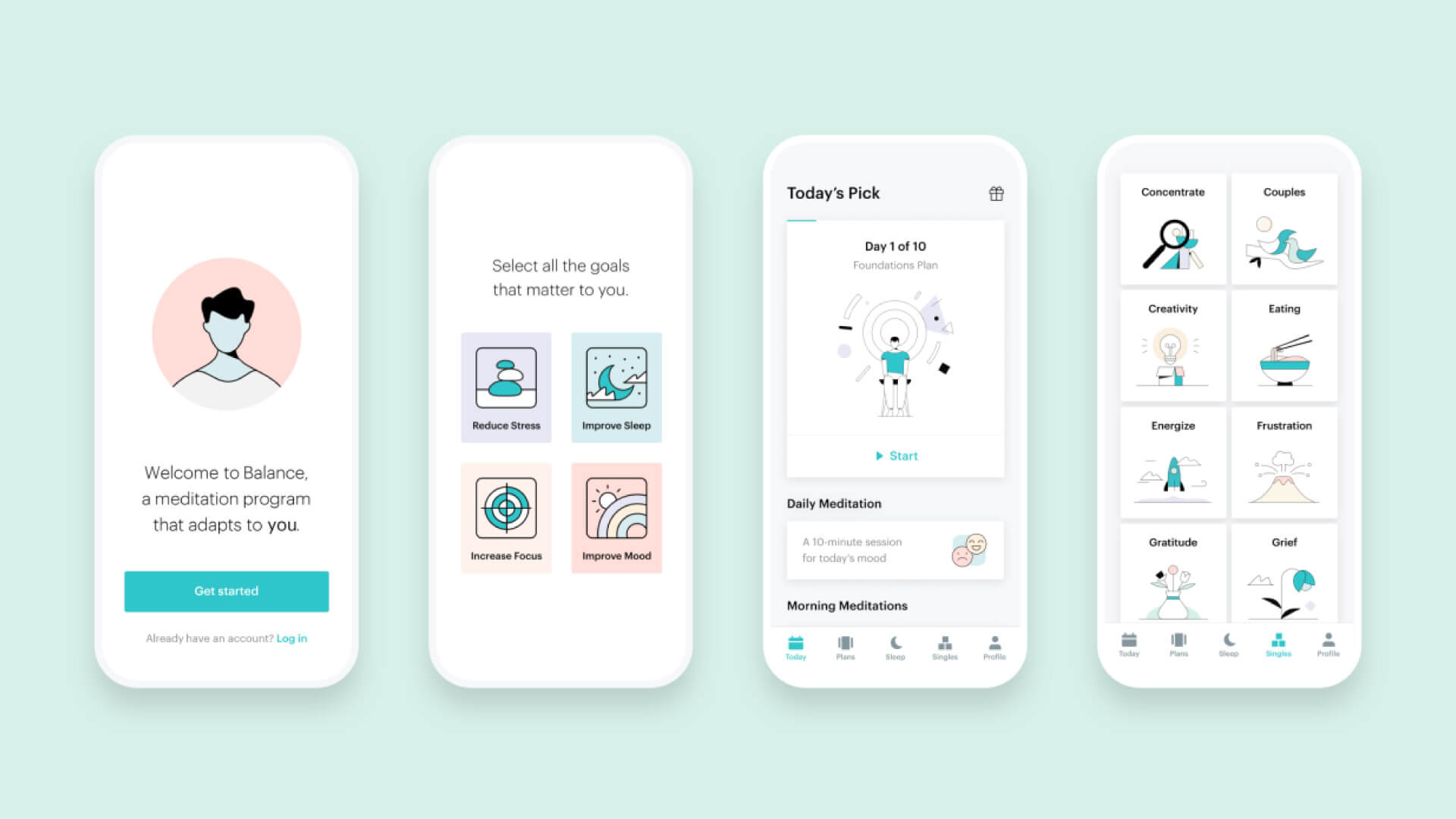

Many apps geared towards promoting behaviour change are also designed around self-determination theory. Health platforms like Pegalo (Previously Quit Genius) on-board users by having them select their personal goals and values, and deliver a personalised experience and content that the user can engage with in their own way at their own pace. Mindfulness products like the Balance App not only track progress and reward users for streaks, they also incorporate social media functionality, allowing mates to see each other’s progress and keep each other accountable.

Tips and Takeaways

When applying motivational science principles to impacting long-term behaviour outcomes, consider these four key takeaways.

Craft opportunities for success and tangible growth

Consider how large, daunting goals can be broken into small, achievable tasks. Offer ways for people to choose their own goal, and track their progress, showing them how far they’ve come. Offering a free or easy win right of the bat, like that first stamp on a coffee card, can help kickstart people into action.

Support choice and agency

Whilst the primary goal of the initiative should be clear, consider how people can customise their journey to change. Whilst too many options at once can cause analysis paralysis, allowing people to make their own choices promotes a sense of agency and ownership in their behaviour.

Leverage social norms and connection

If possible, make a point of showing how many people are already engaging in the desired behaviour. Avoid using words like ‘don’t’, and when recruiting talent or a spokesperson for your campaign, make sure you choose people who your target audience can relate to, or aspires to be like.

Tap into purpose and connection

Try to frame messaging in a way that appeals to your target audiences’ personal values and goals. Tell engaging, human stories. Make the desired behaviour relevant and impactful for something or someone they care about.

Recommended Resources

Behaviour change is a huge topic. We have covered some of the essentials from a design and communications perspective in this article series, but for a more in depth coverage of the topic, see some of these resources.

Engaged: Designing for Behavior Change

This book, by Amy Bucher, Ph.D., explores behaviour change from a digital product perspective. Invaluable for any UX and project designers wanting to use digital interventions to change behaviour.

Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us

A slight reimagining of self-determination theory, Drive, by Dan Pink, explores the fascinating topic of intrinsic motivation through the aspects of Autonomy, Mastery and Purpose.

Perceived Self-Efficacy

This article unpacked the concept of perceived self-efficacy and it’s role in empowering self-motivated behaviour change in a health and wellness context